VARIED PARAGRAPH STRUCTURE

how to keep your sentences from sounding the same

Have you ever been told your prose is repetitive? Dull? Even boring? That type of feedback is tough to take, but if you want to keep your readers engaged, lackluster prose won’t cut it.

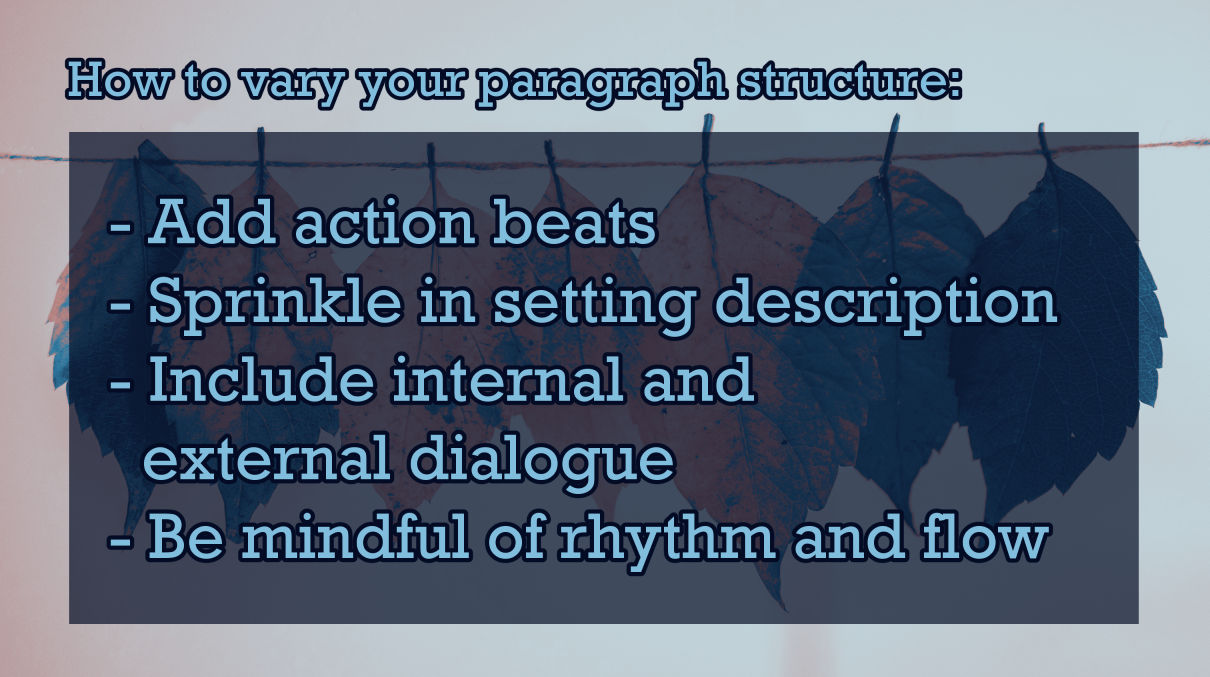

Everyone’s style is different, and as a writer, it can be hard to pinpoint what isn’t working. But if you’ve been told your prose is the dreaded B-word, here’s a good place to start: by varying your sentences. Within a paragraph, varied sentence structure means more than just swapping a clause from the beginning of the sentence to the end—it encompasses a range of crucial writing skills that make up beats, dialogue, and rhythm.

Ready to take your prose from bland to breathtaking? Let’s get started!

action beats

If you find yourself writing a lot of dialogue—especially dialogue of similar length—action beats will be your best friend. These snippets of action can fall before, between, or after lines of dialogue and will spruce up your prose without much effort at all!

Let’s take a look at this first example. Keep in mind that this and all the other examples in this post can be perfectly suitable for certain stories and styles, but for demonstration’s sake we’ll assume that they don’t work in context as-is.

“How was your weekend?” said Joe.

“Oh, just awful. Our dog got out,” said Steven.

“Did you find him?”

“Yeah, he ended up at the dog park we always go to.”

“How do you think he got out?”

“The gate was open.”

“Really? But you’re always so good about locking up.”

“... Between you and me, I think someone did it on purpose.”

This dialogue tells us nothing about what’s going on during the conversation. We don’t know what Joe and Steven are doing, but we don’t know anything about their thoughts and feelings either. We’ll address emotions later on, but for now let’s focus on adding in some action so our reader has something to visualize during this scene.

Joe grabbed his tools and sat at his station. “How was your weekend?”

“Oh, just awful. Our dog got out,” said Steven.

“Did you find him?”

“Yeah, he ended up at the dog park we always go to.”

He pulled on his gloves and grabbed an oyster from his bucket. One swift crack, and he had his first pearl of the day. “How do you think he got out?”

“The gate was open.”

“Really? But you’re always so good about locking up.”

Steven looked up from his work and clutched his knife with a white-knuckled grip. “... Between you and me, I think someone did it on purpose.”

With these edits, the reader knows that Joe and Steven are searching for pearls, and the last paragraph gives us some body language that shows us Steven is still upset about his dog getting out. The action makes it seem more sinister than it was with only dialogue.

Be careful not to use too many action tags, as they can become repetitive if you use the same ones over and over. Try to avoid eye-related action tags, as they are some of the most common, unless (like in this example) the action is meaningful. Some other common action tags are shrugging, nodding, grinning/smiling, sighing, and turning.

narrative beats

Similar to action beats, narrative beats make use of the world around the characters to inject some interest into a scene. Whether it’s the wind blowing, a car driving by, or a giant hole opening up in the ground, these beats are a perfect way to tell the reader about the setting without needing to infodump.

There has to be something he can do. Arnold paces around the living room, pulling his hair and muttering to himself. If he says yes to Jenny, what will happen to his relationship with Hugo? And if he says yes to Hugo, his internship at Boeing is doomed. He circles and circles the couch, and pieces of hair fall on the floor. He goes around hundreds of times—he just can’t stop—until finally his pocket buzzes. It’s Jenny.

In this example, pacing is mentioned multiple times. Remember what I said about action beats becoming repetitive? Let’s try condensing some of these sentences and adding in some narrative beats to make this paragraph more interesting.

There has to be something he can do. Arnold paces around the couch in endless circles, pulling his hair and letting pieces fall to the floor. If he says yes to Hugo, Jenny will never talk to him again; if he says yes to Hugo, his internship at Boeing is doomed. His shoes squeak against the hardwood floor and kids scream outside his living room window, but nothing stops him, not even someone’s horn blasting through the street.

But then his pocket buzzes. It’s Jenny.

This edit uses one more word than the first draft, and it tells us so much more information about the scene. We still know that Arnold is pacing, and that he has a dilemma between Jenny and Hugo, but now we know the intensity of his stress: he won’t even stop to glance outside at the honking cars.

Want some practice? Try adding in a few narrative beats to the first example on this page.

internal & external dialogue

The first example had too much dialogue, but what do you do when you have none? Well, you add some, of course!

External dialogue is when one or more characters talk out loud. Internal dialogue refers to the point-of-view character’s thoughts (also known as internal monologue/narration). Generally, all scenes—and sometimes all paragraphs—need internal dialogue, but not all scenes need external dialogue. Let’s check out the example below and see what we should add.

He finds Bryce in the kitchen and the kid wants cereal for breakfast. They eat at the counter and Bryce goes on about his science fair project, something to do with magnets and electricity. He eats his breakfast and tells Bryce to hurry up, and finally they’re out the door, still a few minutes late.

This reads to me like a rushed scene. It’s entirely made of narrative summary, which is a useful tool for unskippable yet uninteresting information, but the voice tells us that the point-of-view character is feeling something: annoyance. We aren’t told this, and we’re barely shown it. A combination of external and internal dialogue as well as action beats should be able to rescue this excerpt!

He finds Bryce sitting at the kitchen counter.

“Can I have cereal for breakfast?” the kid says, swinging his feet.

Goddammit. He’s old enough to get his own food. But he pours Bryce a bowl and grabs a banana from the fridge, and as much as he wants to put on his headphones and listen to his podcast, he sits next to him at the counter and eats.

“We’re working on science fair projects this week,” says Bryce. “Mine’s on magnetic fields. You know, they can make electricity!”

“Uh huh.”

“James and I are gonna make a generator with Mr. Fredrick. I wonder if we can take some of the electricity home.”

“Uh huh.”

“Do you think we can?”

“Finish eating, okay?”

He throws away his banana peel and thank God, the kid finally shuts up. But he only has a few moments of respite before they get in the car and his mouth starts going again.

By tracking the blue text, you can see how I’ve kept the same information from the original while expanding upon it. See how much the scene has changed? The point-of-view character is obviously annoyed by Bryce, given his non-answers and internal dialogue. Maybe they’re just late, or maybe he’s babysitting Bryce for his stuck-up cousin and he’s taking out his frustration on him. Either way, this excerpt has been completely transformed by a little thing called show, don’t tell—which is something we’ll dive into in another blog post.

rhythm and flow

This sentence is short. It provides emphasis.

This sentence is longer, but not too long. Medium-length sentences make up the bulk of paragraphs.

This sentence is particularly lengthy, and some may say you are required to break it up or a copyeditor will do it for you, but I disagree. Long sentences contribute to the flow of a paragraph, and if you’re writing for adult audiences, there’s no reason to limit yourself to short- and medium-length sentences just because the “average” length of a sentence tops out at 20 words.

Unless you’re trying something experimental, most paragraphs need all types of sentences. Short sentences work well at the beginnings and ends of paragraphs, while long sentences tend to work well in the middle. Medium-length sentences can fill out the rest.

But my word isn’t law—the best way to see if your paragraphs flow is to read them out loud. If you trip up when speaking, your readers will too. If you don’t want to read it yourself, you can use a text-to-speech software like NaturalReader and kick back while you listen to them read your story aloud.

On a final note, use punctuation to your advantage. You can manipulate how someone reads your sentences by choosing the right type and amount of punctuation, and you can even make extremely long sentences easy to read by putting your expert punctuation skills to good use.

Now, let’s get into this example.

Rebecca walked out of the store with her arms full of groceries. She thought: what a beautiful day. The sun shone on her face and there was hardly a cloud in the sky. She needed to get home and put the groceries away before she could pick up Johnny from school, but she wanted to stand there in the sun as long as she could.

This paragraph contains two medium sentences, one short sentence, and one long sentence. In theory, that seems like a good spread, but if you read the paragraph out loud, you can see how clunky and bland it is. Let’s use all the skills we’ve learned to give this excerpt some personality.

Rebecca walked out of the store with her arms full of groceries. What a beautiful day; the sun warmed her cheeks and the birds chirped in the oak trees lining the parking lot. There was hardly a cloud in the sky! If only she could sit in the grass and sunbathe all day… but she needed to put the groceries away at home before she could pick up Johnny from school. Still, another minute in the sun wouldn’t hurt.

Here, I’ve added setting description and internal dialogue that helps ground the reader in the scene. I’ve also punctuated the excerpt with a short sentence, giving it closure, and I used a semicolon and an ellipsis to guide the rhythm of the prose.

Rhythm and flow can be difficult to conceptualize, and I recommend you read, read, read in order to get the hang of it. Try reading your favorite book out loud and see how much you learn!