REPETITION: BEATING DEAD HORSES

how to spot repetition in your writing and what you can do to fix it

Repetition, repetition, repetition. Although it has its uses as a literary device, unedited repetition in prose can cause your writing to feel overexplained and boring. There’s nothing titillating about reading the same sentence three times in a row written in slightly different ways.

If we want our prose to pull our reader in and our stories to move along quickly, we have to learn how to spot different kinds of repetition (even the sneaky kinds!) and what we can do to fix it.

problem: individual words

It’s easy to pluck the same old words out of your vocabulary bucket to get on with writing your first draft. We all do it, and it can really speed up the writing process. But when you’re ready to line edit, it’s time to pay attention to those bland, repeated words and swap them out for language with more voice and personality.

Strong words make for strong prose, but the strength of an individual word is diminished the more you use it. Certain types of words like articles and pronouns will rarely be a problem even when repeated dozens of times on a single page, but a unique word like “saccharine” will stand out amongst the rest. When used once in a while, a perfect, rare word can seriously elevate a sentence.

But if “saccharine” comes up three times on a single page, people will notice, and they’ll wonder why you’re using such a specific word so often. Usually these words are the candy of our prose, and too much candy can make us sick or put us off of a certain sweet forever. We don’t want to make our readers nauseous—well, most of us don’t!

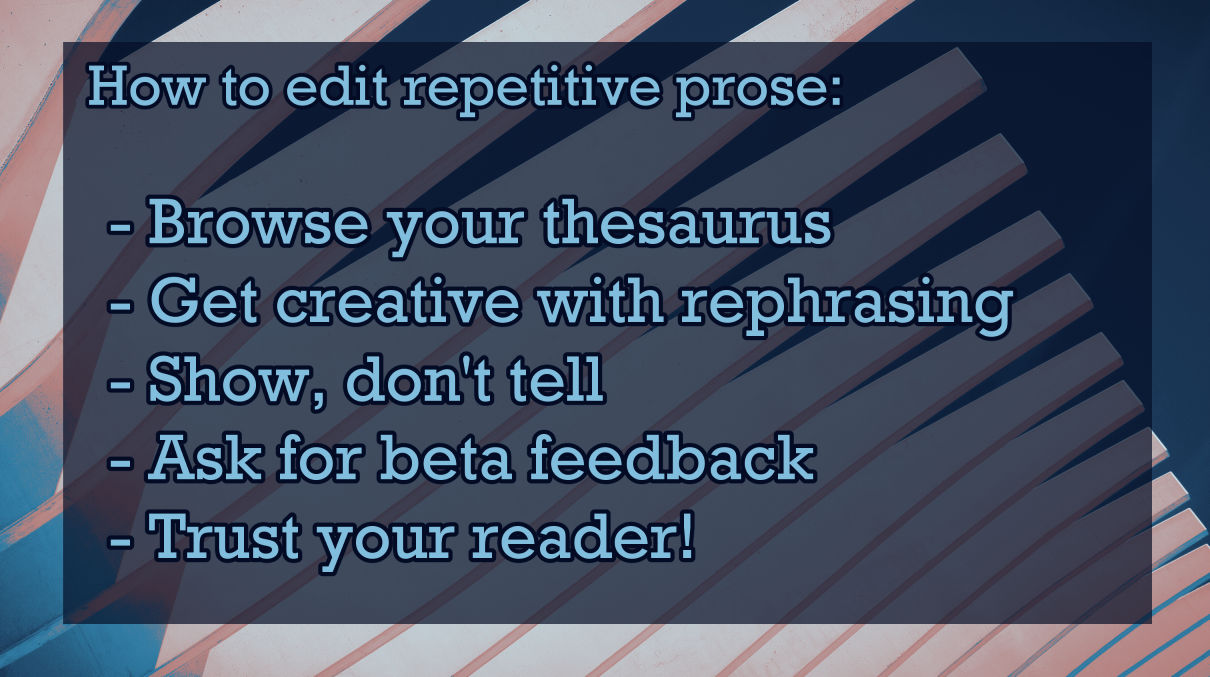

fixes: thesaurus and rephrasing

The thesaurus is a valuable tool in every writer’s bookmarks bar. There are always more words to learn, and sometimes we just can’t remember a word that’s on the tip of our tongue. There’s no point in wasting time trying to think of it—pull up your thesaurus and put it to use!.

In some cases, the thesaurus is all you need to cut repetition from your sentences.

The sun’s golden hue blankets the valley in glittering gold.

The sun’s yellow hue blankets the valley in glittering gold.

This sentence is a perfect candidate for a synonym. We can’t use the same color in this sentence twice, but if we took out “gold hue”, the flow of the sentence would change, so we need to find a synonym. Here, you have to decide which noun is more important—which one should be described as “gold”—and I chose the valley because it’s unlikely the sun is the true subject of our narrative.

Let’s try something a little more complex.

They drove down the long, winding road, and their long trip was far from over. All along the road, dandelions spread their seeds in a puff of white as they sped by, and Jason stared out the window, wondering how much longer this trip would take.

In this paragraph, multiple words are repeated several times. Let’s try the same trick and use the thesaurus to switch these up without changing anything else.

They drove down the vast, winding road, and their lengthy trip was far from over. All near the street, dandelions spread their seeds in a puff of white as they sped by, and Jason stared out the window, wondering how much longer this excursion would take.

I’m sure you saw this coming: our reliance on the thesaurus turned this paragraph into meaningless soup. When the same words are repeated multiple times in quick succession but used in different ways, the best option is to take a step back and look at the paragraph as a whole. What can we take out? Can some sentences be rephrased? What can we add to improve the paragraph in terms of internal dialogue, narrative beats, and action beats?

They drove down the winding road, their trip far from over. Dandelions grew in the dirt beside the pavement, and the car sped by them, spreading their seeds in bursts of white, the air full of cotton as pale as his mother’s clammy, motion-sick face. Jason rested his arms on the windowsill and watched the fuzzballs fly past. When would they get to Grandma and Grandpa’s house?

Much better. When you start to learn your patterns of repetition, you’ll be able to skip straight to writing this second-draft prose, bypassing the monotony altogether. Reading helps with this—there’s no better way to expand your vocabulary than by reading books!

problem: pet phrases

Pet phrases are words and phrases that writers inadvertently overuse. Anything can be a pet phrase, but these often come up in action tags and stage directions. Ever read a character sigh ten times in a single chapter? That’s a pet phrase.

Although action tags like sighing and shrugging are common in all stories, even unique tags can become pet phrases. If a character picks his nails when he’s nervous, this can be used as an emotional tell, but if you start putting the same tag all over your story without the accompanying emotion, it loses its meaning and wears on the reader.

fixes: rereading and creativity

In order to fix your pet phrases, first you have to be aware of them. You can reread your prose yourself, but you may accidentally skip over these phrases because you’re so used to them. Some writing softwares such as Scrivener will show you which words you use most often, but it won’t flag repeated phrases. For an advanced analysis of your writing, you can turn to Bookalyzer, which will flag pet phrases, adverbs, and a slew of other places where your prose might be lacking.

If you have the funds, you can also hire an editor to do the heavy lifting for you. They will be able to look at your writing with fresh eyes, and any repetition will jump right out at them to polish. Alternatively, you can try asking your writing Twitter friends to swap manuscripts for critique, but bear in mind it can be a lot of work to line edit an entire novel!

Once you’ve discovered your pet phrases, it’s time to get creative. Line editing is always a long process, and if you have a lot of repeated phrases in your writing, you’ll need to sit and think about ways to replace them. Like above, you may have to restructure sentences or paragraphs, or you may be able to remove the phrases in some cases. Whatever you choose, try to challenge yourself to think of things you don’t write or read often. Those unique phrases will make your writing a joy to read.

“I feel stuck.” Robert sighed. “What am I supposed to do? I’m out of options.”He didn’t want to hurt his friend’s feelings, but the right choice seemed obvious. He shrugged and looked away. “I think it’s time to talk to Casey.”

“What?” Robert gasped. “I can’t do that!”

He cocked his head. “I think you can.”

In this example, there are several overused action tags to replace that I wrote about in this post. Can you spot them?

“I feel stuck.” Robert ran his hands through his hair and tugged. “What am I supposed to do? I’m out of options.”He didn’t want to hurt his friend’s feelings, but the right choice seemed obvious. He watched a bird fly into a nearby tree just so he didn’t have to see Robert’s face when he said: “I think it’s time to talk to Casey.”

“What?” Robert stomped his foot. “I can’t do that!”

“I think you can.”

Here, we’ve used all the fixes. We replaced phrases, restructured and added sentences, and removed some altogether. All of these replacements are a product of show, don’t tell, which is at the core of most prose-focused advice. If you want to level up your showing skills, I recommend reading Understanding “Show, Don’t Tell” by Janice Hardy.

problem: implied actions, thoughts, and feelings

Some types of repetition are sneaky. As I mentioned in my post about stage directions, some actions, thoughts, and feelings speak for themselves without needing additional explanation—even dialogue can be all you need to flesh out a scene sometimes.

If you take the advice from the first point and swap out your repetitive, bland words for strong, active words, your sentences will say everything they need to say on their own. But we often find ourselves tacking on adverbs or extra sentences to explain things that we’ve already said.

fixes: show, don’t tell

I hope by now you’re learning to love “show, don’t tell”, because it can fix many of your problems with repetition. To remove tells, all you need to do is determine what part(s) of your sentences are doing the work and make sure the supporting information enhances it rather than distracts from it.

Consider a sentence like:

“I hate you!” he yelled angrily.

The yelling implies that he is angry—we can remove that repetitive adverb. But we can take it a step further and remove the yelling too because the sentence is punctuated with an exclamation point. By cutting out these repetitive words, we allow the reader to envision the scene for themselves and immerse themselves in the story. They get to imagine what the character is doing and what they look like while they’re saying their dialogue without having to adhere to the stage directions you’ve given them.

It’s normal to want to give your reader as much specific information as possible, like telling them exactly what your characters are doing with their bodies while they speak or walk, or even to specify emotions to make sure your readers know how they feel without a shadow of a doubt. But part of the fun of reading is getting to read between the lines, and if you overexplain, your readers won’t have a chance to use their imaginations.

Let’s tackle a longer excerpt.

In his post-dream haze, he considered letting the phone go to voicemail. The successes and failures of the previous day came flooding back as the ringer blared in his ear, tossing the blankets away and quickly rolling onto his other side. John propped himself up with his elbow and cleared his throat, hovering his hand over the phone with anxiety. He took a deep breath and grabbed the handset. “John’s Housekeeping, how can I help you?”

This passage comes directly from the first draft of one of my novels. It’s not terrible, but there’s a whole lot of nothing happening even though I’m telling the reader a lot. If we change some of that telling to showing, our readers will have a lot more fun.

He lay there in his post-dream haze as the phone rang, rubbing his forehead. Yesterday—that’s right. He’d started and ended the day without a job, and now was his chance for success. But his heart thumped against his ribs with every ring, and he rolled over, chewing his bottom lip. Staring. Waiting until the last second.“John’s Housekeeping, how can I help you?”

By taking out the repetitive “telling”, we saved 13 words, and now the reader can come to their own conclusions about John’s emotions. We showed them that his heart is thumping and he’s chewing his lip—telltale signs of anxiety. There’s no need for the deep breath or any of the moving around in bed because the jump to dialogue shows us that he decided to pick up the phone, although we do tell the reader that he waited until the last second. If we were to show that piece of information by counting out the six or so rings before the voicemail started, readers would roll their eyes. Sometimes a little bit of telling is the right choice—you just need to know when to make it.

problem: repeated information

This problem is on a larger scale than the previous ones. Instead of being a line editing problem, repeated information tends to be a developmental editing problem. You can repeat anything on a small scale, but what I’m talking about here is plot or character information that comes up multiple times in a story in the same way without any growth.

Sometimes we want to make sure a particular piece of information comes across to our readers, and we can overcompensate by dropping that information into the story as many times as possible. As tempting as it is (no one wants to be misunderstood!), any seasoned reader will notice repeated information, and they will likely feel bored and potentially condescended by the assumption that the author doesn’t believe in their ability to remember or put together parts of the story.

This happened to me when I was reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Murakami dropped some obvious hints early on in the book about what the main character's wife had gone through in her childhood, and I quickly picked up on it. The more I read, the more was revealed, but no new information was added. By the end of the book, I was told outright that my assumption was correct, and there was nothing else to it. If it was supposed to be a mystery, he gave me way too much information! And if it wasn’t, I was dissatisfied because he didn’t expand upon the information—he simply kept stating it over and over.

Of course, it’s just as dissatisfying to not have enough information throughout the course of a story and suddenly have everything revealed to you by the author in a way that you couldn’t have possibly put together. Information management is an art of its own and the best advice I can give in this post is to make sure that if you’re repeating something, you’re revealing something else along with it. Maybe it’s character motivation, thematic messages, or something to move the plot along. Whatever it is, just make sure you’re expanding, not repeating!

fixes: feedback

As much as I wish we could, it’s impossible to read our stories for the first time as a reader would. We’ll always know what’s coming, so there’s no way for us to be certain whether we’ve put too much or too little information into our stories. Thus, you need to look to your peers for help.

There are lots of places to make friends with other writers who can give you a hand with your manuscript, as stated above. All of those suggestions apply here, but if you’re looking for feedback on information management specifically, I recommend creating a Google Form with questions your beta readers can fill out after they read your story. Ask questions about repetition, like:

Could you see the ending coming?What did you expect to happen when X, Y, Z?

Were you bored at all during the story?

Were you confused by any character motivations?

Was there anything you didn’t understand?

With their help, you should be able to spot repetition and cut out the sections that say a little too much. Your story will be more interesting and captivating if you take the time to give it the editing it deserves!

If your draft is full of repetition like the examples I’ve given here, don’t fret! Books go through several rounds of editing before publication, and I can assure you most authors have lots of repetition to cut after their first—or fifth—draft. I hope this post gives you some insight into how to tackle repetition with confidence.