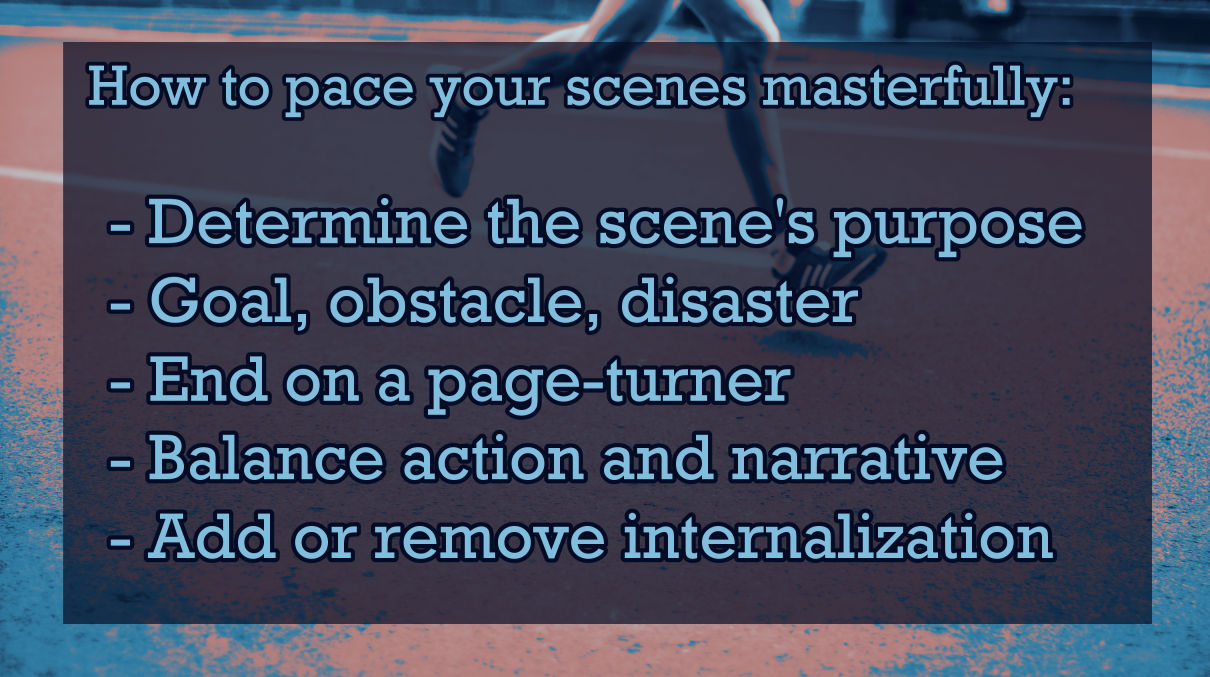

MASTERING SCENE PACING

learn how to write scenes that flow effortlessly

Scene pacing is difficult even for a seasoned writer. In the moment, it’s hard to see how your scene connects to the story around it, and in turn, it’s even harder to know if it flows while you’re still drafting.

After you write your first draft, it’s inevitable that you’ll have pacing problems, whether on a large or small scale. But by learning the basics of scene pacing, you can improve your foresight and catch pacing problems before they’re written, cutting back on things you need to fix in the edit. Your edits will take less time, too!

determine the scene’s purpose

Before you start writing a scene, even if you’re a pantser, it’s essential to determine the scene’s purpose. Without purpose, our scenes will meander aimlessly and we’ll be doomed to cut and rewrite for eternity.

Say we’re writing a campy horror novel about two girls who become stranded in a snowy cabin and have to find a way back home before a demonic grizzly bear eats them alive. Exciting, I know. Our first scene may take several different forms. We could start while the girls are planning their trip, before they even get to the cabin. Maybe they had originally booked a stay in a different cabin, but that one got double-booked so they have to take a different one that they don’t realize is infested with demon bears. Maybe we start at the moment they enter the cabin, and the girls can find suspiciously bear-like footprints around the back entrance. Maybe we start on the trip there and the girls see a large animal in the trees on their drive up the mountain.

All these potential opening scenes serve the same purpose: to introduce our readers to the main characters, show them the setting, and foreshadow the main conflict. But wait—that’s not one purpose, that’s three! And thank goodness for that.

Rarely will you have a scene that serves only a single purpose. The best scenes serve two to five different purposes, but more or less than that can become troublesome. If a scene serves only one purpose, your story may be too straightforward and your readers will be able to see what’s coming like they’re looking through a pane of glass. Too many purposes and the scene will feel scattered, unfocused, and like it has no purpose at all. List the top two to five things you want to accomplish with your scene and use that as a foundation while you write. Keep this list nearby to make sure you stay on track.

Sometimes we have to discover the purpose of our scenes along the way. That’s okay, as long as you’re willing to circle back during your edits and determine the scene’s purpose later. If you finish your manuscript and you still can’t find a purpose for some of your scenes, you might want to consider cutting them altogether. It’s better to have a shorter story where every word counts than a longer one that readers might abandon because of its aimless wandering. If you can’t tell why something is happening, neither can they!

goal, obstacle, disaster/resolution

I learned the goal/obstacle/disaster formula from Jack Bickham’s book Scene and Structure, which I highly recommend if you want to know more about scene pacing. The concept is simple: in every scene, we need the main character to have a goal, which they are unable to achieve because of an obstacle, and this obstacle leads to a disaster that takes them further away from their overall story goal. By determining these three aspects, we can create a loose scene outline.

Let’s start with our scene goal, which is different from its purpose in that the goal is focused on the POV (point-of-view) character. Instead of looking at the scene from a structural perspective, we’re now looking at it from a plot perspective.

In our snowy horror novel, we need to write a scene in which the girls split up to look for resources that can get them home. Girl 1’s task is to walk down the road and see if she can find any neighbors. Girl 2’s task is to venture into the basement and look for something they can use to signal their distress.

Let’s say we want to write in Girl 2’s POV. Her task’s goal becomes the scene goal: find something in the basement to help them get home. But throughout most of your story, your characters will only partially complete their goals, at best. That’s where obstacles come into play.

We can’t allow Girl 2 to find the radio that is secretly stashed in the corner of the basement, therefore we need to introduce an obstacle that will keep her from finding it. This obstacle has to be intense enough to disturb her from her task while not being so intense that the story suddenly goes off the rails. Let’s say that while she searches, she can hear heavy footsteps upstairs and scratching on the cellar door, which scare her out of the basement before she is able to finish her search.

This obstacle leads directly into the scene’s disaster: a place for the scene to end that takes our main characters further away from their overall story goal. In this novel, the characters’ story goal is to get home alive, and a disaster should impede them from getting home, staying alive, or both. If a bear shows up at the back door, Girl 2’s life will be threatened and she will have no way to warn Girl 1, who is out looking for help. She will also be unable to find the radio, which means both of the story goals are in jeopardy.

Later in your story, your disasters will turn into resolutions. At some point near the end, things will start to go right for the character, and instead of telling them “no”, you can finally say “yes”!

ending the scene

Your goal as a writer is always to get your reader to turn the page. Therefore, the beginning of the next scene is just as important as the end of the scene you’re currently writing. In one way or another, your ending has to propel the reader into the next scene, which is most easily done with a cliffhanger.

A cliffhanger can convince your reader to continue a few pages into the next chapter before they stop for the day. They’ll be so curious about what’s going to happen next, it’ll be almost impossible for them to stop at the end of the chapter, put down your book, and never pick it up again. In general, your reader will continue reading as long as the story interests them and it maintains a lively momentum. Even the most interesting stories will be dropped when the pace stumbles and faceplants.

Let’s consider the end of our horror scene. Girl 2 has separated from Girl 1, explored the basement to no avail, and heard banging upstairs. She goes to investigate and behold: she comes face-to-face with a demonic, bloodied grizzly bear the size of a pickup truck.

… And then the scene ends.

What happens to Girl 2? Does the bear come after her? Did the bear already eat Girl 1? Are they doomed?

Of course not. Our reader is only quarter of the way through the story—there’s lots more chaos that needs to unfold! The reader knows this, and they will peek ahead at the next chapter even though they’re done reading for the day, just to see if Girl 2 survives.

But here’s the catch: we write the next chapter in Girl 1’s POV. By doing this, we can extend the reader’s interest by enticing the reader to read even more so they can eventually get back to Girl 2.

If you don’t know how your current scene will begin, it can be helpful to determine the ending and move backward from there—especially if you’re writing your first scene. By deciding on an ending that will keep your readers reading, you can plan out the rest of your scene in a way that will slowly speed up toward the end and launch them into the next chapter, rather than landing softly and giving the reader a reason to put your book down.

Although dramatic cliffhangers are a useful way to keep your story moving, too many of them can wear on the reader. Another way to keep the momentum is to make sure you leave your reader with a question at the end of the chapter. A question can be something immediate, like “Will Girl 2 die?” but it can also be something deeper that the reader has yet to discover, like “Where did the demonic bears come from?” An internal revelation can move the story along just as well as a terrifying image.

balancing action and narrative

Let’s recap the bones of the scene we’re planning:

Scene purpose: Separate main characters, explore basement, introduce demon bearsGoal: Find something to signal distress

Obstacle: Mysterious noises upstairs

Disaster: Demon bear at the back door

Outline:

Girl 1 and Girl 2 split up to find resources separately

Girl 2 explores the basement in search of a radio

Scratching and thumping upstairs startles Girl 2, and she investigates

She discovers a demon bear is trying to get into the cabin

We’ve done the easy part. Now we have to look at our scene as chunks of dialogue, action, narration, and internalization, which is where most writers stumble. While dialogue and action speed the story up, narration and internalization slow it down. This doesn’t mean that you should strive to cut out as much narration and internalization as possible, but rather that you need to know where to put it and how much of it to use.

Let’s take each beat of our outline and expand upon it.

Girl 1 and Girl 2 split up to find resources separately.

By nature, this part of the scene needs dialogue. We’ll see the main characters decide on their goals, split up the tasks, and go their separate ways. We can pad that out with a touch of internalization here and there to set the tone by showing how nervous Girl 2 is to be left alone in the cabin. This part of the scene should move along briskly.

Girl 2 explores the basement in search of a radio.

Here is where we run into trouble. Girl 2 is alone, so she has no one to talk to but herself. We run the risk of diving into narration and internalization and bringing the scene to a halt as we watch her peer around every corner and dust off boring old shelves. To keep this part of the scene moving, we must create a mysterious and creepy atmosphere to inject tension into an otherwise slow scene.

Although internalization slows us down further, we can’t shy away from it. Internalization gives us the opportunity to break up paragraphs of narration with Girl 2’s unique voice. Instead of spending two pages discovering old knick-knacks with her, we can get deep into her mind and learn more about her while she sorts through the basement junk. Every so often, she can step on a squeaky floorboard or see something in the shadows, just to keep the reader on their toes.

Scratching and thumping upstairs startles Girl 2, and she investigates.

When things seem safe, just before the scene gets too slow, we bring in the action. We need to cut back on the internalization, but not completely, because Girl 2 needs to decide what she’s going to do in the face of danger. We need to go through her options quickly and use strong word choice to increase the tension.

She discovers a demon bear is trying to get into the cabin.

At the end of the scene, things speed up. We swap internalization for action to keep things moving, and we spend a little more time describing Girl 2’s physical and mental reaction to fear rather than her interpretation of what’s going on—we can get back to that later, after the action is over. Then, we leave the scene on a cliffhanger: the image of the demon bear.

internalization to augment scene pace

So, how do you manipulate scene pacing yourself? It takes practice and editing, but the best tool you can use to augment pacing is internalization.

As we discovered, internalization slows down the pace of a scene. Every time your character has something happen to them, they need to debrief with themselves about it, which results in chunks of action, internalization, and reaction, not always in that order.

In a fast-paced scene, our characters don’t have time to internalize. Something happens to them, and they react. Later, when they’re cooling off, we can sneak in the internalization from earlier to give the reader and the characters some time to breathe.

Let’s skip ahead a few chapters in our story. After Girl 2 finds the bear, she reacts by grabbing a shotgun from the mantle and running outside. She finds Girl 1 and saves her from the bear by shooting it until it backs off. During this sequence, there’s little time for internalization—maybe a line here or there.

But later, when the main characters are eating cans of soup by the fire, Girl 2 can think or talk about how terrified she was when she was fighting the bear, and how scared she was that Girl 1 was going to get hurt. By pushing back the internalization, we set up a subsequent scene (which Jack Bickham calls a sequel) and we keep the pace moving where we need it: during the action.

If you ever feel like your story is moving too slowly, try cutting out some internalization. And if it’s moving too quickly, try adding some. Maybe you skipped it in a previous scene and now’s the chance for your character to think about the past or future to aid their decision-making.

putting it all together

To solidify your understanding of pacing, I’ve written the scene we outlined in this article and annotated it to explain my storytelling choices. This is by no means a perfect scene, but you’ll be able to see how to take the outline we created and turn it into a full-fledged scene! Click here to read it.