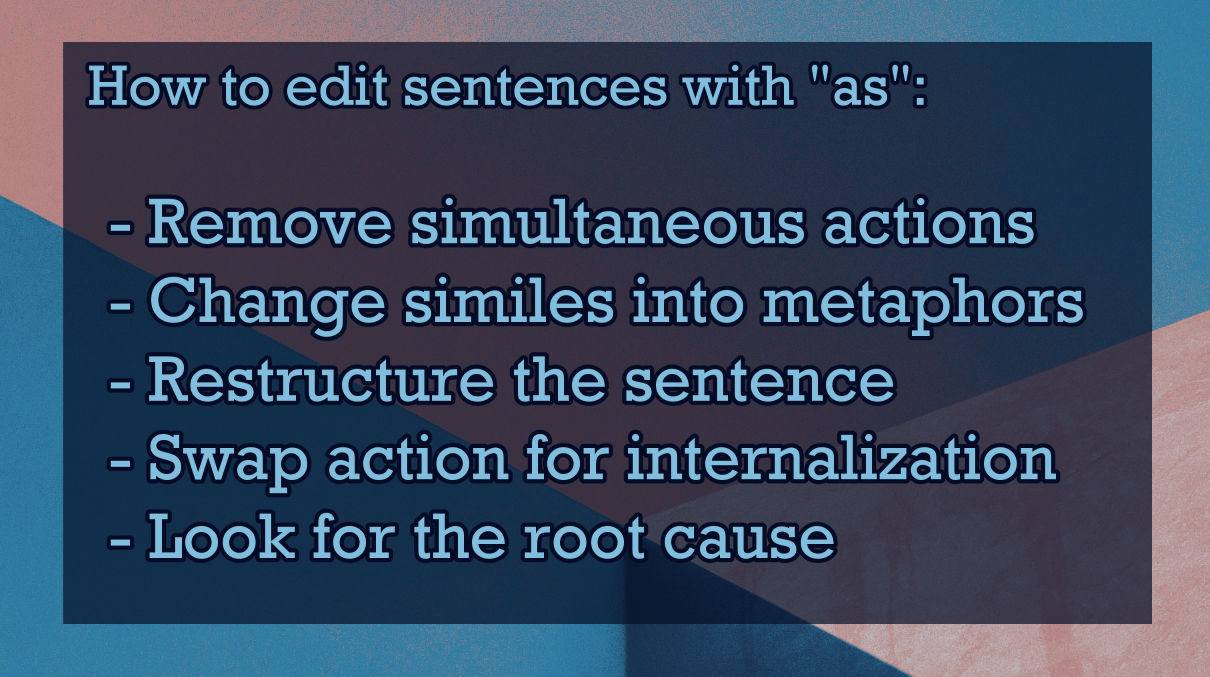

WHIP YOUR "AS" INTO SHAPE

quick and easy tips to minimize the use of “as” in your writing

What’s so bad about “as”, huh? To the untrained eye: nothing. It’s a versatile word with many uses, and it exists for good reason.

But if you’re like me, you may have started to notice a pattern in your writing. In fiction, we string together actions connected by “as”, and they make sense to our drafting minds, so we keep doing it. And doing it. And doing it.

And suddenly every sentence you write has an “as” or three.

Before long, “as” is no longer just useful—it becomes a crutch. You may end up with hundreds of instances of “as” in your prose if you aren’t careful, and too much of anything is always a reason to sound the editorial alarms. But how do you fix something so tiny, so innocuous? Where do you draw the line between harmless usage and muddied clauses that confuse the reader?

In this article, we’ll take a look at the wide variety of ways you can use “as” and I’ll teach you how—and when—to remove them from your prose.

grammatical usage

Like many words in the English language, “as” falls under multiple categories in grammar. It can be an adverb, conjunction, pronoun, preposition, or even a seldom-used noun. These are all completely valid ways to use this word; my goal in this article is to make you aware of new ways to write sentences without “as” so you can feel confident while you edit, not to scare you away from the word itself.

Our friends at Merriam-Webster have a comprehensive definition that lists all the possible uses for “as”. Most of these definitions are self-explanatory. If you find a usage that lists alternate words or phrases, you are free to swap them in for “as” wherever you see fit, but it may not solve whatever the root problem is with your sentence. There’s no need to memorize these definitions or to learn which part of speech you’re using every time you write “as”, but being aware of the terminology can help you identify where you lean on “as” most often.

simultaneous actions

The door closed as she went inside.

This is one of the most common uses of “as” that I see in fiction. In this construction, “as” creates simultaneous actions, and often us writers don’t realize that the actions we’ve chosen can’t physically happen at the same time until we go back and edit our work. For instance:

She laughed as she said, “You’re so funny!”

You may be able to get these words out while laughing if you try very hard, but it’s more likely that your speech will be unintelligible. To solve this issue, simply replace “as” with “and”. While “as” signifies that two things are happening at the same time, “and” lets the reader know that two things have happened one after another—which is far easier to understand in a story than multiple actions that happen simultaneously.

Here’s a longer example from one of my drafts:

He shut the car door slowly as he turned to leave, then headed across the grass toward the bathroom. His boots squelched as he waded through the mud, as if he were walking across the killing floor of a slaughterhouse, and as he ducked into the standalone bathroom, a bead of cold sweat ran down his cheek.

This excerpt is drowning in “as”! See how easy it is to rely on “as” when you’re drafting? We have simultaneous actions that don’t make much sense and unnecessary adverbs that weaken similes. It’s time to get out the scissors and cut some of this bullshit.

He shut the car door slowly and headed across the grass toward the bathroom. His boots squelched through the mud, the ground beneath him sticky and slippery like the killing floor of a slaughterhouse, and as he ducked into the standalone bathroom, a bead of cold sweat ran down his cheek.

In this edit, we removed the action of “turning” entirely to get rid of two things at once: overused stage direction and a simultaneous action. We also restructured the second sentence to transform the conditional clause into a stronger simile. But wait, you say—you forgot the last one!

Like most line editing decisions, my choice to leave the last “as” is entirely subjective. However, I do have two reasons for it: now that the paragraph is stripped of extra instances of “as”, there is room to leave one without succumbing to repetition; also, the simultaneous actions in this part of the sentence can reasonably happen at the same time. It takes no effort to let a bead of sweat run down your face while you do anything, so these actions get a passing grade and can be left alone. If you had other instances of “as” to get rid of, you might want to consider changing it, but there’s usually no harm in leaving one every so often.

Keep your eyes peeled for actions like these and ask yourself whether or not they make sense together. If not, substitute “and” or restructure the sentence. You’ll almost always come out the other side with a stronger sentence.

similies

Her fleece was white as snow.

Another way to use “as” is in similes. This literary device can level up your prose, but relying on the same construction over and over is no better than not using them at all. If you need to take “as” out of a simile, you can sometimes replace it with “like” without changing anything else in the sentence.

Her fleece was white like snow.

In this example, the meaning of the sentence is slightly warped by the use of “like”. Instead of telling us that the fleece is exactly the same—“white as snow”—the fleece is now adjacent to the color: “white like snow”. Instead, consider this construction:

In many cases, there’s no need to eliminate your similes, but if you find yourself reaching for them too often, you may have fallen into a pattern of repetition. Line editing will be your friend in this scenario, and you’ll need to pay close attention to every sentence—and the sentences surrounding it—to optimize flow, word choice, tone, and a dozen other attributes I’ll cover in future articles.

Another option that can come in handy is to turn your similes into metaphors. Although similes are strong tools on their own, metaphors are heavy lifters and sprinkling them here and there can make your writing more unique. This strategy doesn’t work for every simile, depending on the sentences around it, and you’ll need to be able to trust your editorial ear when making this replacement.

Say you have this line:

Waves crashed against the jetty as loud as cracks of thunder.

This simile falls a bit flat. We want prose that hits us like these waves hit the rocks, but by the time I get to the end of this sentence, I don’t feel frightened. We’ve all heard this comparison before, and it’s lost its meaning. We get it—the waves are loud. If we come up with a more impactful way to get the point across, our readers will be caught off guard and the waves will hit them harder.

Waves crashed against the jetty in cracks of thunder.

Now the imagery is more visceral. Instead of comparing the waves to thunder, the waves are thunder, and the reader will imagine thunder alongside the waves, not just heavy waves similar to thunder.

But we’re never going to edit a single line out of context. Let’s look at the original simile within a paragraph:

George rushed down the dock, clutching his life preserver and hat to his chest. Where was Stella? The storm was only getting worse! Waves crashed against the jetty as loud as cracks of thunder. He wiped rain from his eyes and squinted out at the sea, his heart pounding against his ribs, and then he saw it: her bright yellow ribbon bobbing in and out of the water.

What do you think? Does the simile fit? Should we swap it with the metaphor? Maybe we need something else entirely, or we need to move the sentence to a different part of the paragraph for flow. Here’s what I would do:

Violent waves slammed against the jetty in deafening cracks. George rushed down the dock, clutching his life preserver and hat to his chest. Where was Stella? The storm was only getting worse! He wiped rain from his eyes and squinted out at the sea, his heart pounding against his ribs, and then he saw it: her bright yellow ribbon bobbing in and out of the water.

I wanted this sentence to end on the strongest word—crack—so I restructured the sentence to accommodate it, which naturally eliminated the simile. Then I moved the sentence to the beginning of the paragraph to establish tone first and foremost. With that out of the way, I’m able to dedicate the rest of the paragraph to George and his search for Stella without distracting the reading by tossing in more atmosphere.

What would you have done?

examples

Learning where to eliminate “as” takes time and practice. Here are several examples with explanations on the changes I made, but remember: line editing is a subjective art and these edits are my editorial suggestions only. My word isn’t law.

She wanted to be an inspiration to as many of them as she could.

She wanted to inspire them all.

The original sentence has many extra words that don’t give us new information. To cut down on how verbose it is, I determined the goal of the sentence—to tell the reader she wants to inspire many people—and kept it simple. In doing so, I was able to cut out “as”.

She peered down the street as far as possible.

She peered far down the street, straining her neck.

In this sentence, I wanted to show instead of tell how far she was looking. By adding the second clause and removing “as”, the reader gets a better sense of the effort it takes for her to do the action.

Her voice grew softer as she continued, “I think you should leave.”

Her voice softened. “I think you should leave.”

There are two issues to tackle here: “as” and repetition. The dialogue shows us that she is continuing to speak, so there’s no need to tell us too. By removing that clause and swapping out “grew softer” for “softened”, we save on even more words while completing our two goals.

He shoved past her, wrinkling his nose as the scent of smoke hit him.

He shoved past her and the scent of smoke hit him, wrinkling his nose.

This is a common simultaneous-action construction. The reader needs to know about the smoke hitting him before learning that he wrinkles his nose because in real life we wouldn’t respond to the scent before actually smelling it. I replaced “as” with “and” and swapped the two actions to revise this issue.

However, I’m still not satisfied with this sentence. The participial phrase “wrinkling his nose” is a common action beat that tells us little about the character’s thoughts and feelings. I want to bring more life to this sentence, and I can do so by getting creative with my beats and splitting this into two sentences.

He shoved past her and the scent of smoke hit him. Gah—it was like a cigarette addict’s wet dream.

Now we know the character thinks the smoke is disgusting and he hates cigarettes. If you have the opportunity to add internal dialogue instead of an action beat, my recommendation is always to try it. Action beats are useful, but internal dialogue tells us a lot more.

leaving “as” alone

It bears repeating that “as” isn’t always the real problem in a sentence. Some sentences are too long, and “as” is stringing together several actions that should be broken up. And some sentences use “as” without any issues at all. If you try to remove “as” and it’s not getting you anywhere, leave it alone—it’s probably doing no harm.

Here are some examples where “as” does its job better than any other word could:

As his mother would say, “It’s all in your head.”

In a few hours, his own skin would become as inhospitable as the scrap metal car, and none of his selfish customers would even bother to say “I’m sorry” to his miserable face.

The smell seemed to be emanating from it, releasing from its fibers as the rug baked in the sun.

If he mentioned Burson Road, with its piss-stained concrete and broken windows, she wouldn’t see him as a human; no, he’d take on the form of a diseased dog—one that just spent four hours spreading his filth all over her carpet.

Did you notice that I didn’t use “as” a single time in this article outside of quotations? It just goes to show how many other ways there are to construct a sentence with the same information!

I’ll leave you with an excerpt you can test yourself on. Remember there’s no one true way to edit a passage. Everyone’s interpretation will be unique!

It was noon when the bus arrived, and as Jack stepped onto the sidewalk, a boy on a skateboard zoomed by. He lost his footing and stumbled into a bush outside his house, waving his fist in the kid’s direction.“Hey! Say you're sorry!” he yelled as he brushed leaves off his pants.

The boy looked over his shoulder as he turned a corner and held up his middle finger.

Jack groaned. It was as if today was the worst day of his life.